Confessions of a (post) SharePoint architect: Black belt platitude kung-fu

Hello kung-fu students and thanks for dropping by to complete your platitude training. If you have been dutifully following the prior 5 articles so far in this series, you will have now earned your yellow belt in platitude kung-fu and should be able to spot a platitude a mile away. Of course, yellow belt is entry level – like what a Padwan is to a Jedi. In this post, you can earn your black-belt by delving further into the mystic arts of the (post) SharePoint architect and develop simple but effective methods to neutralise the hidden danger of platitudes on SharePoint projects.

If this is your first time reading this series, then stop now! Go back and (ideally) read the other articles that have led to here. Now in reality I know full well that you will not actually do that so read the previous post before proceeding. Of course, I know you will not do that either, so therefore I need to fill you in a little. This series of articles outline much of what I have learnt about successful SharePoint delivery, strongly influenced from my career in sensemaking. I have been using Russell Ackoff’s concept of f-laws – truth bombs about the way people behave in organisations – to outline all of the common mistakes and issues that plague organisations trying to deliver great SharePoint outcomes.

So far in this series we have explored four f-laws, namely:

- f-Law 1: The more comprehensive the definition of governance is, the less it will be understood by all

- f-Law 2: There is no point in asking users, who don’t know what they want, to say what they want

- f-Law 3: The probability of SharePoint success is inversely proportional to the time taken to come up with a measurable KPI

- f-Law 4: Most SharePoint governance objectives are platitudes. They say nothing but hide behind words

In the last post, we took a look at the danger of conflating a superlative (like biggest, best, improved and efficient) with a buzzword like (search, portal, collaboration, social). The minute you combine these and dupe yourself into thinking that you now have a goal, you will find that your project starts to become become complex, which in turn results in over-engineered solutions solving everything and anything, and finally your project will eventually collapse under its own weight after consuming far too many financial (and emotional) resources.

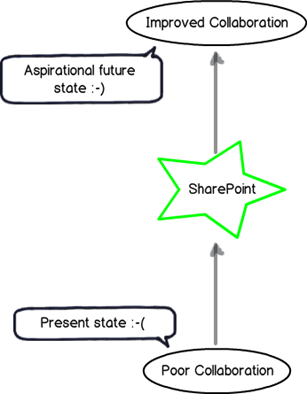

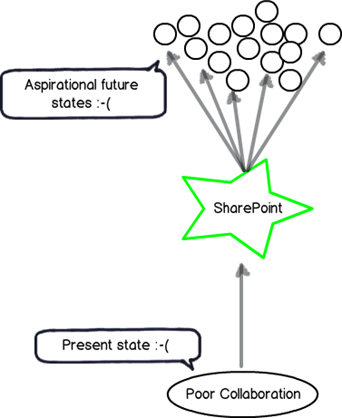

This is because the goal you are chasing looks seductively simple, but ultimately is an illusion. All of your stakeholders might use the same words, but have very different interpretations of what the goal actually looks like to them. The diagram that shows the problem with this is below. On the left is the mirage and to the right is the reality behind the mirage. Essentially your fuzzy goal actually is a proxy for a whole heap of unaligned and often unarticulated goals from all of your stakeholders.

Now in theory, you have read the last post and now have a newly calibrated platitude radar. You will sit at a table and hear platitudes come in thick and fast because you will be using Ackoff’s approach of inverting a goal and seeing if a) the opposite makes any logical sense and b) could be measured in any meaningful way. As an example, here are three real-world strategic objectives that I have seen adorning some wordy strategic plans. All three set off my platitude radar big time…

“Collaboration will be encouraged”

“A best-practice collaboration platform”

“It’s a SharePoint project”

I look at the first statement and think “so… would you discourage collaboration? Of course not.” Ackoff would take a statement like that and say “Stop telling me what you need to do to survive, and tell me what you need to do to thrive”.

What do you mean by?

So if I asked you how to unpack a platitude into reality, what might you do?

For many, it might seem logical to ask people what they really mean by the platitude. It might seem equally logical to come up with a universal definition to bring people to a common understanding of the platitude. Unfortunately, both are about as productive as a well-meaning Business Analyst asking users “So, what are your requirements?”

With the “what do you mean by [insert platitude here]” question, the person likely won’t be able to articulate what they mean particularly well. That is precisely why they are unconsciously using the platitude in the first place! Remember that a platitude is a mental shortcut that we often make because it saves us the cognitive effort of making sense of something. This might sound strange that we would do this, but in the rush to get things done in organisations, it is unsurprising. How often do you feel a sense of guilt when you are reflecting on something because it doesn’t feel like progress? Put a whole bunch of people feeling that way into a meeting room and of course people will latch into a platitude.

By the way, the “mental shortcut” that makes a platitude feel good seems to be a part of being human and sometimes it can work for us. When it works, it is called a heuristic, When it doesn’t its called a cognitive bias. Consult chapter 2 in my book for more information on this.

Okay, so asking what someone means by their platitude has obvious issues. Thus, it might seem logical that we should develop a universal definition for everyone to fall in behind. If we can all go with that then we would have less diversity in viewpoints. Unfortunately this has its issues too – only they are a little more subtle. As we discovered in part 2 of this series appropriately entitled “don’t define governance”, definitions tend to have a limited shelf life. Additionally, like best-practice standards, there are always lots of them to choose from and they actually have an affect of blinding people to what really matters.

So is there a better way?

It’s all in the question and its framing…

If there is one thing I have learnt above all else, is that project teams often do not ask the right question of themselves. Yet asking the right question is one of the most critical aspects to helping organisations solve their problems. The right question has the ability to cast the problem in a completely different light and change the cognitive process that people are using when answering it. In other words, the old saying is true: ask a silly question, get a silly answer.

Let me give you a real life example: Chris Tomich is a co-owner of Seven Sigma and was working with some stakeholders to understand the rationale for how content had been structured in a knowledge management portal. Chris is a dialogue mapper like me – and he’s extremely good at it. One thing Dialogue Mapping teaches you is to recognise different question types and listen for hidden questions. The breakthrough question in this case when he got some face time with a key stakeholder and asked:

- What was your intent when you designed this structure for your content?

The answer he got?

- “Well, we only did it that way because search was so useless”

- “So if I am hearing you, you are saying that if search was up to scratch you would not have done it that way”

- “Definitely not”

Neat huh? By asking a question that took the stakeholder back to the original outcome sought for taking a certain course of action, we learnt that poor search was such a constraint they compensated by altering page template design. Up until that point, the organisation itself did not realise how much of an impact a crappy search experience had made. So guess where Chris focused most of his time?

In a similar fashion, my platitude defeater question is this:

So if we had [insert platitude here], how would things be different to now?

Can you see the difference in framing compared to “what do you mean by [insert platitude here]?”. Like Chris with his “What was your intent”, we are getting people to shift from the platitude, to the difference it would make if we achieved the platitude. No definitions required in this case, and the answer you will get almost by definition has to be measurable. This is because asking what difference something would make involves a transition of some kind and people will likely answer with “increased this” or “decreased that”.

Now be warned – a hard core middle manager might serve you up another platitude as an answer to the above question. To handle this, just ask the question again and use the new platitude instead. For example:

- Me: Okay so if you had improved collaboration, how would things be different to now?

- Them: We would have increased adoption

- Me: And what difference would that make to things?

I call this the KPI question because if you keep on prodding, you will find themes start to emerge and you will get a strong sense of potential Key Performance Indicators. This doesn’t mean they are the right ones, but now people are thinking about the difference that SharePoint will make, as opposed to arguing over a definition. Trust me – its a much more productive conversation.

Now to validate that these emerging KPI’s are good ones, I ask another question, similarly framed to elicit the sort of response I am looking for…

What aspects should we consider with this initiative to [insert platitude here]?

This question is deliberately framed as neutral is possible. I am not asking for issues, opportunities or risks, but just aspects. By using the term aspects I open the question up to a wider variety of inputs. Like the KPI question above, it does not take long for themes to emerge from the resulting conversation. I call this the key focus area question, because as these themes coalesce, you will be able to ensure your emerging KPI’s link to them. You can also find gaps where there is a focus area with no KPI to cover it. As an added bonus, you often get some emergent guiding principles out of a question like this too.

The thing to note is that rather than follow up with “what are the risks?” and “what should our guiding principles be?”, I try and get participants to synthesize those from the answers I capture. I can do this because I use visual tools to collect and display collective group wisdom. In other words, rather than ask those questions directly, I get people to sort the answers into risks, opportunities and principles. This synthesis is a great way to develop a shared understanding among participants of the problem space they are tackling.

If we were unconstrained, how would we solve this problem?

This is the purpose question and is designed to find the true purpose of a project or solution to a problem. I don’t always need to use this one for SharePoint, but I certainly use it a lot in non IT projects. This question asks people to put aside all of the aspects captured by the previous question and give the ideal solution assuming that there were no constraints to worry about. The reason this question is very handy is that in exploring these “pie in the sky” solutions, people can have new insights about the present course of action. This permits consideration of aspects that would not otherwise be considered and sometimes this is just the tonic required. As an example, I vividly recall doing some strategic planning work with the environmental division of a mining company where we asked this exact question. In answering the question, the participants had a major ‘aha’ moment which in turn, altered the strategy they were undertaking significantly.

Note: If you want some homework, then check Ackoff’s notion of idealised design and the Breakthrough Thinking principle called the purpose principle. Both espouse this sort of framed question.

Sharpening the saw…

Via the use of the above questions, you will have a better sense of purpose, emergent focus areas and potential measures. That platitude that was causing so much wheel spinning should be starting to get more meaty and real for your stakeholders. For some scenarios, this is enough to start developing a governance structure for a solution and formulating your tactical approaches to making it happen. But often there is a need to sharpen the saw a bit and prioritise the good stuff from the chaff. Here are the sort of questions that allow you to do that:

No matter what happens, what else do we need to be aware of?

This question is called the criterial question and I learnt it when I was learning the art of Dialogue Mapping. When Dialogue Mapping you are taught to listen for the “no matter what…” preamble because it surfaces assumptions and unarticulated criteria that can be critical to the conversation and will apply to whatever the governance approach taken. Thus I will often ask this question in sessions, towards the end and it is amazing what else falls out of the conversation.

What are the things that keep you up at night?

I picked this up from reading Sue Hanley’s excellent whitepaper a while back and listening to hear speak at Share2012 in Melbourne reminded me why it is so useful. This question is very cleverly framed and is so much better than asking “What are your issues?”. It pushes the emotive buttons of stakeholders more and gets to the aspects that really matter to them at an gut level rather than purely at a rational level. (I plan to test out dialogue mapping a workshop with this as the core question sometime and will report on how it goes)

What is the intent behind [some blocker]?

This is the constraint buster question and is also one of my personal favourites. If say, someone is using a standard or process to block you with no explanation except that “we cannot do that because it violates the standards”, ask them what is the intent of the standard. When you think about it, this is like the platitude buster question above. It requires the person to tell you the difference the standard makes, rather than focus on the standard itself. As I demonstrated with my colleague Chris earlier, the intent question is also particularly useful for understanding previous context by asking users to outline the gap between previous expectation and reality.

Conclusion…

To there you go – a black belt has been awarded. Now you should be armed with the necessary kung-fu skills required to deflect, disarm and defeat a platitude.

Of course, knowing the right questions to ask and the framing of them is one thing. Capturing the answers in an efficient way is another. For years now, I have advocated the use of visual tools like mind mapping, dialogue mapping and causal mapping tools as they all allow you to visually represent a complex problem. So as we move through this series, I will introduce some of the tools I use to augment the questions above.

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

Leave a Reply