Confessions of a (post) SharePoint Architect: Don’t define “governance”

Hi all and welcome to the second post of a series that I have been wanting to write for a while. In this series, I am going to cover some of the lesser considered areas of being a SharePoint architect and by association, key aspects to SharePoint governance. In the first confessional post I alluded to the fact that a good SharePoint architect also need to architect the right conditions for SharePoint success. As I work through this series of articles, I will elaborate further on what those conditions are and how to go about creating them.

To do this, I am drawing from my non IT work as a Dialogue Mapper and facilitator, and where applicable, will cover these case studies to see if they give us any insights for SharePoint. I also hope to dispel some common myths and misconceptions about SharePoint project delivery in organisations. Some of these might challenge some notions you hold dear. But for the most part, I hope that many of you reading this find this material to be instinctively compatible with what you have already come to believe. If you are in the latter group and feel as if you are an organisational agitator, this just might give you that rigour and ammo that you need when getting through to the powers that be. Better still, tell them to read this series and let them decide for themselves.

Backstory: Ackoff and f-Laws

For what it’s worth, a fair chunk of this material comes from my book, as well as the first module of my SharePoint Governance and Information Architecture class that I run a few times a year in various places around the world. When I designed that class, I was inspired by Russell Ackoff, who co-wrote a funny and highly readable book called “Management f-LAWS: How organisations really work”. F-Laws were defined as:

“truths about organisations that we might wish to deny or ignore – simple and more reliable guides to everyday behaviour than the complex truths proposed by scientists, economists, sociologists, politicians and philosophers”

In case you hadn’t noticed, if you remove the hyphen, each f-law become a flaw. You could also consider them as #fail laws. Years ago, I laughed and at the same time, inwardly cringed when I read each f-Law that Ackoff and his co-authors had come up with. I came to realise that SharePoint problems are simply a microcosm of broader issues that plague organisations. If you read Ackoff’s book (and I highly recommend it), you will soon realise that the word “Management” could easily be substituted with “SharePoint” and it doesn’t take much to come up with a few of your own f-laws. This is exactly what I did and at last count, I have 17 of them. In this post, I will detail the very first one.

F-Law 1: The more comprehensive the definition of governance is, the less it will be understood by all

The first condition that I need to design as a SharePoint architect is to put to bed the many misconceptions about SharePoint governance. In this f-Law, I state that the more you try and define what SharePoint governance is, the less anybody will actually understand it. If you consider this counter-intuitive, then let me take it even further. For any project that has a change management aspect (SharePoint projects often are), definitonising not only doesn’t work, but it is actually quite dangerous to your projects health.

To explain why I have come to this conclusion, I’d like to tell you a little story from my non IT work. Several years ago, I was working in a sensemaking capacity with an organisation to help them come up with a strategic plan and performance framework for a new city. This was not a trivial undertaking. The aim was to create a framework with an aligned set of KPI’s to realise the vision for what the city needed to be in the year 2030. While the vision for the city had been previously agreed and understood, the path to realise that vision had not been.

Now if you have ever been involved in strategic plan development, and think that working out your corporate strategy is difficult, I have news for you. Aligning an organisation to a 3 year plan is one thing. Working with a diverse group to determine performance measures of a future city 25 years away is a different thing altogether. I never realised at the time we did this work, just how unique and (dare I say) “cutting edge” it was. Participants were highly varied in skills and areas of interest, and to say each had their own world-view was an… understatement to say the least.

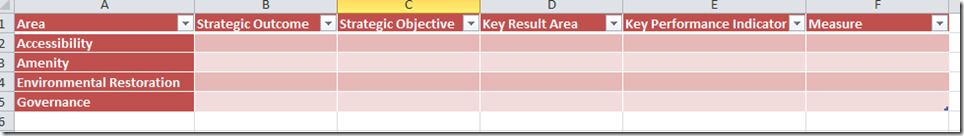

I my book I describe this case study in detail but for the sake of post size, let’s just say that the opportunity to do this work arose from a failed first attempt to create the framework. The first time around an excel spreadsheet was projected onto the wall that looked like the example below. Attempts were made in vain to fill in the strategic outcomes, strategic objectives, key result areas, key performance indicators and measures. After a frustrating few hours of trying this approach, we gave up because participants spent all of their time arguing over the labels and got bogged down in a tangle of definitions and ambiguous terminology. Was it a KPI (Key Performance Indicator) or a KRA (Key Result Area)? Was it a Guiding Principle or a Strategic Objective? Was it a KRA or a Critical Success Factor? Attempts to resolve this issue with definitions got nowhere because even the definitions could not be agreed upon.

In the end, we solved this issue via a rather novel use of Dialogue Mapping along with a problem structuring approach outlined in a book called Breakthrough Thinking. If you’d like to know more on how it was done, then take a look in chapter 12 of the Heretics Guide.

The criticality of context…

The core problem boiled down to context – or lack of it. What I learnt from this is that in situations without a shared context (and the wrong tools to deal with it), we fall back to using definitions to try and fill the gap. When faced with a blank spreadsheet and just some labels, participants attention was fixated on the definitions of the labels, rather than the empty cells where the focus needed to be. This resulted in a bunch of long winded discussions about what terms meant. This seriously stymied efforts aimed at making progress.

I have since performed many workshops, both SharePoint and non SharePoint ones and the pattern is clear. In fact I contend that if you proceed down the road of trying to build context via definitions for complex problems, one of three things will happen.

- The definition becomes more verbose. There are a couple of reasons for this:

- – The definition is expanded to incorporate new aspects of the topic space. In an organisational setting, this creates confusion because the definitions of multiple disciplines can often seemingly contradict each other and thus, careful “wordsmithing” is required to navigate a path through it.

- – New qualifications or exceptional situations have to be excluded. This leads to more new terms being used in the definition.

- As a result of #1, a broader, fundamental definition is developed. This broader definition encompasses more and so is prone to motherly sounding platitudes. Further, such definitions also run the risk of being interpreted in ways other than the one intended by those who worked so hard on the definition.

- As a result of #1 and #2, a new word is used or an existing word is used in a new context to try and convey the new meanings or concepts proposed. I have heard governance described as “stewardship”, “risk management” and (guilty as charged), “assurance”.

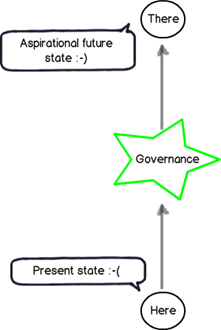

The effect of this can be far reaching in a bad way because definitionising has a habit of blinding people to what really matters. This leads to terrible project decisions being made up front that have serious consequences. To understand why, consider the image below:

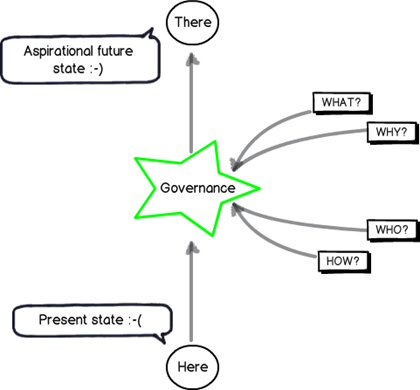

This image represents how governance of a SharePoint project should be viewed. A SharePoint initiative takes time and effort which costs money. We presumably have recognised that the present state is lacking in some way and want to get to somewhere better – an aspirational future place (if you look closely in the left above image note the happy and sad smilies). Accordingly we accept the cost of deploying SharePoint because we believe it will make a positive difference by doing so. If this was not the case, you would be wasting your time and resources on a pointless initiative. Therefore, it is the difference made by the initiative that will tell you if you have succeeded or not. As a result, we have to have a shared context on what that aspirational future looks like!

Don’t confuse the means with the ends…

Governance is, therefore, the means by which you will achieve the end of getting to some better place. It is informed by the end in mind and this is why I drew it in the star in the middle of the above diagram. For example; If the end in mind was compliance, then I will govern SharePoint a heck of a lot differently than say, if the end in mind was improving collaborative decision making.

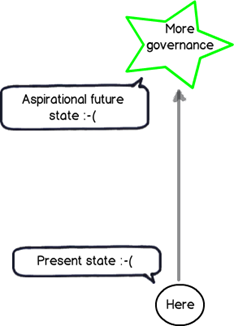

But consider the diagram below. In this context, it should be clear why working from a definition of governance is often problematic. It implies that:

- Governance is not being informed by the end in mind;

- Your team do not have a shared understanding of what the end in mind actually looks like.

When this happens, project teams rarely realize it and respond by substituting the end with the means. We overly focus on governance via definition without any clarity or context as to what the aspirational future state actually is. Like the example of the blank spreadsheet example I started with, reality starts to look more like the diagram below: (note the happy smilie is gone now)

Steering…

So how do we steer out of this definition pickle? Interestingly “steer” is a appropriate choice of word if we look at the origin of the word “Govern”. This is because “Govern” is a nautical term from Latin and actually means “to steer”. So if your SharePoint project has been more like the Titanic, and hit a giant iceberg along the way, then clearly you need to focus your governance efforts to looking at what is in front of you, rather than scrubbing the deck or keeping the engine room well oiled. The latter tasks are important of course, but you can do all that, still hit an iceberg and waste a lot of money.

To steer, we all have to understand what the destination is, or at the very least, all agree on the direction. To help you with that journey, consider my final diagram. To steer SharePoint the right way for your organisation requires you to answer four key questions:

- What is the aspirational future state and what does it look like?

- Why is this the aspirational future state we want?

- Who will do what to get us to that state?

- How will we get to that state?

The fundamental problem with most SharePoint projects is that questions 1 and 2 are not answered sufficiently, if at all. The next few posts will explore why this is the case, but in the meantime, remember that we could do a SharePoint project that is to scope, time and cost, yet still have no user up-take if we are solving the wrong problem in the first place. Therefore remember that:

- Governance is a means to an end, and not the end in itself.

- We shouldn’t undertake a “SharePoint governance” project, or consider “SharePoint governance” as deliverable on a project plan. The act of developing a shared context of what the problems are and using that to always steer the governance decision making is paramount. Failure to do this and and your best plans will not save you.

Conclusions and coming next…

This is the second post on what will be a large series – possibly the largest series I have written so far. In the next post in this series, I will continue into our journey of SharePoint governance mistakes and along the way, start to identify what we can do to better answer the “What”, “Why”, “Who” and “How” questions. If you enjoy this series, then consider signing up to one of my classes if one is running in your neck of the woods.

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

Nice post mate, sometimes I feel like I’m back at bloody university reading your blog posts. Even SHIFT-F7 doesn’t come up with some of the words you use in here!

I like where you are going with this. My approach is to spell out what the future states should be and work backwards in a way to identify some business processes that can get to those future states.

I agree with you that fundamentally Microsoft & the community have not done a great job of explaining what the possible outcomes can be of a better future state.

I’m in this series you don’t get too bogged down in “why it goes wrong in answering these questions” and instead focus on what this future state can be. This is much more useful to the reader base who can then use these future states as their future state. Granted its different between organizations, but concepts are fundamentally the same.