The facets of collaboration part 4–BPM vs. HPM

- The facets of collaboration Part 1–Meet robot barbie

- The facets of collaboration Part 2–Enter the matrix!

- The facets of collaboration Part 3-The feature jigsaw

- The facets of collaboration Part 4 – BPM vs. HPM

- The facets of collaboration Part 5 – It’s all Gen-Y’s fault – or is it?

Hi all and welcome to part four of my series on unpacking this buzzword phenomenon that is “collaboration”. Like it or not, Collaboration is a word that is very in-vogue right now. I see it being used all over the place, particularly as a by-product of the success of x2.0 tools and technologies. Yet if you do your research, most of the values being espoused actually hark back to the 1950’s and even earlier. (More on that topic in my forthcoming Beyond Best Practices book).

As it happens, Dilbert is quite a useful buzzword KPI. Once a buzzword graces a Scott Adams cartoon, you know that it has officially made it – as shown below:

So back to business! Way back in the first article, I introduced you to Robot Barbie, a metaphor that represents all of those horrid SharePoint sites remind you of a cross-dressing Frankenstein’s monster. I had an early experience with a client who championed a particular vision for a SharePoint project, only to find little buy-in within the organisation for that vision. This, and a bunch of other things, got me interested in the softer areas of SharePoint governance, where no tried and tested best practices really exist. If they did and were so obvious, Microsoft would published them as its in their interest to do so.

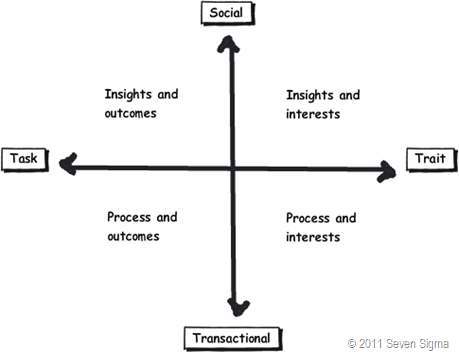

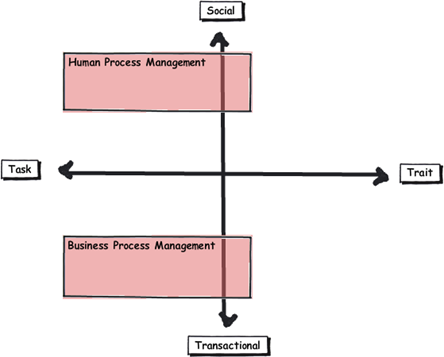

This all culminated in when I wrote a SharePoint Governance and Information Architecture training course last year. I read a lot of material where authors attempted to unpack what collaboration actually meant. My rationale for doing so would be to hopefully avoid creating SharePoint solutions that were Robot-Barbie Frankensteins. The model that I came up with is illustrated below:

The basic model is covered in detail in part 2. But to recap here is the basic summary: This model identifies four major facets for collaborative work: Task, Trait, Social and Transactional.

- Task: Because the outcome drives the members’ attention and participation

- Trait: Because the interest drives the members’ attention and participation

- Transactional: Because the process drives the members’ attention and participation

- Social: Because the shared insight drives the members’ attention and participation

In the last post, I used the model to compare and contrast the use of particular SharePoint features, such as wikis, SharePoint lists and the different aspects of document collaboration. With regards to the latter of these three, I l looked at the effectiveness of certain SharePoint building blocks like content types and site columns within the different facets.

In this post and the next, we will use the facets in a different manner. We will take a quick tour through some common philosophical smackdowns that manifest in organisational life. These smackdowns emanate because of the different viewpoints that people with particular job titles and respective bodies of knowledge have.

Any suggestion that a philosophy might be wrong or incomplete often calls into question the self-identify of the practitioner, which causes much angst among adherents. For this reason, I will leave the “agile is great” vs. “agile sucks” debate for another time, because if you search the internet for criticisms of agile you tend see really passionate programmers get all riled up and flame the hell out of you.

Instead, I will start with a relatively easy one…

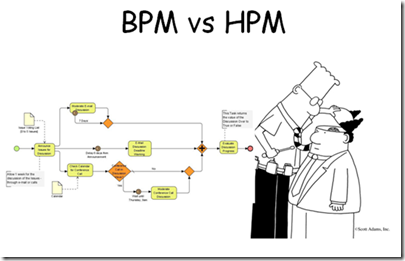

Business Process Management v.s. Human Process Management

What does painting the Golden Gate Bridge and Business Process Management have in common? With both, you find that by the time you get to the end, you need to go back to the beginning again. I have personally seen organisations fill an office full of people and take literally years to define and then document key processes all in the name of various best practice frameworks or a regulatory requirement. They then find that, once a thick process manual is created, no-one actually follows it unless an auditor is watching or their performance-based remuneration is directly measured by adherence to it. Of course, I’m not the only one to notice this. In fact, the entire discipline of business process management has taken a bit of a battering in recent years.

If we consider a “process” as the means by which we convert inputs of some description into outputs, Business Process Management has long been the discipline that concerns itself with process optimisation. But in a pattern that is seen in all disciplines like Project Management and Business Analysis, someone will inevitably come along, tell you that you have it wrong or are not being “holistic” and invent a new term to account for your wrongness. In the case of BPM, we now have people arguing for various terms: such as Human Interaction Management, Human Centric Business Process Management, Non-Linear Business Process (thanks Sadie!) or Human Process Management. We will use the latter term, but they are essentially talking about the same thing.

So before we see an example Human Process Management (HPM), let’s review Business Process Management and see what the HPM fanboys are whining about.

Business Process Management

BPM is a structured approach to analyse and continually improve and optimise process activities. Process structure and flow are modelled via diagrammatic tools, allowing organizations to abstract business process from technology infrastructure and organisational departmental/jurisdictional boundaries. This abstracted view allows business to holistically examine process and increase their efficiency and respond rapidly to changing circumstances. This in turn creates competitive advantage.

BPM is often used within the broader context of process improvement methodologies such as Six Sigma (which if you have never read about it, will finally prove to you that all that high-school mathematics that you found mind-numbingly boring was actually useful). While BPM on its own provides excellent visibility of process via modelling them, Six Sigma also incorporates additional analytical tools to solve difficult and complex process problems. Thus, BPM and Six Sigma augment each-other, because process improvement efforts can be more focused via BPM modelling. Thomas Gomez, in an article entitled “The Marriage of BPM and Six Sigma", had the following to say:

“Without BPM, Six Sigma may flounder because executives lack the critical data needed to focus their efforts. Instead, the executives bounce all over the place looking for performance weaknesses, or they focus on areas where successful performance improvements provide only marginal results. With BPM, Six Sigma projects can pinpoint problems and address the underlying causes.”

But that is where the fun ends according to the BPM critics. BPM nerds have had to suffer the indignation of hurtful labels like “Sick Sigma” and stories of long term problems with innovation because of such initiatives. They cite examples such as George Buckley of 3M, who wound back many of his predecessor’s Six Sigma initiatives.

"Invention is by its very nature a disorderly process. You can’t put a Six Sigma process into that area and say, well, I’m getting behind on invention, so I’m going to schedule myself for three good ideas on Wednesday and two on Friday. That’s NOT how creativity works."

Ouch! Its enough to make a BPM feel all flustered and defensive of their craft. Nevertheless the above quote echoes the main points made by BPM critics. That many processes are not structured, predictable or logical and therefore, BPM approaches force a structured paradigm when none necessarily exists (Mind you, many other methodologies do precisely the same). In an appropriately titled article “The H-Bomb of Business Processes: Humans”, Ayal Steiner makes a point that also cuts to the heart of tame vs wicked problems debate too.

“The modern idea of BPM stresses a well-defined business process as the starting point but this is not always the case. Therefore, in a project that involves new practices or a cross-functional learning among participants, BPM has always had a tough time dealing with the humans.”

The notion of the well-defined starting or ending point is one of the characteristics of a tame problem. Wicked problems are often characterised by poorly defined staring and ending points. In fact with a wicked problem, often participants cannot agree on what the problem is in the first place!

Critics like Steiner also argue that many roles within an organisation, tend to deal with more tacit, dynamic situations and as such spend a large amount of their work time performing collaborative human work, when compared to transactional business process work (knowledge workers is the prevailing label for this type of role). While the main area of benefit for BPM’s is its ability to increase the efficiency of a core business process, the sort of thinking required to re-think processes in a systematic manner involves collaboration and systems thinking (in other words, beyond the process in front of us and how it interacts and interrelates more broadly since the whole of the broader system is greater than the sum of its parts). This is a human-driven activity as it is based on humans collaborating and innovating.

Closer to SharePoint home, Sadie Van Buren noted this same distinction in May 2010 which was around the same time I started the development of my IA class.

Human Process Management

So if BPM is incomplete, enter Human Process Management (HPM). HPM is concerned with process that is not easily defined, nor well structured, where it is hard to prescribe the execution of the process based on some model of the business. With human process, it is generally known how to achieve an intended result, but each case is handled separately and requires tacit judgment (for both decisions and flow) as part of the process. There is not enough standardization between instances of the process that allows for a formal, complete and rigorous description of the process end-to-end.

The obvious downside of human processes, say the critics, is that they are far too fluid and dynamic to be made part of an Enterprise BPM system. As a result, these processes tend to be handled through email, which in turn contributes to information overload and poor information worker productivity – precisely why we look to tools like SharePoint in the first place! The implication of HPM is that we need to shift emphasis to tools and practices that help us deal with unstructured or ad-hoc processes (and the information created/used during that process) more so than tools that deal with the well-defined world of BPM.

To be fair to the BPM crowd, these above criticisms will be seen by BPM practitioners as naive, since from their point of view, the less structured side is simply a part of the entire BPM spectrum. They argue that critics do not properly understand the principles and philosophy of BPM in the first place (Agile and PMBOK defenders say essentially the same thing when defending from critics). Supporting this counterargument is a key theme for BPM success that is regularly emphasised. That is, the critical pre-requisite of clarity of purpose and shared understanding of the end in mind. Mohamed Zairi, in a paper called “Business process management: a boundaryless approach to modern competitiveness” stated:

“The achievement of a BPM culture depends very much on the establishment of total alignment to corporate goals and having every employee’s efforts focused on adding value to the end customer.”

Therefore the BPM crowd are arguing for the same human process that HPM base their criticism on. Developing a culture of alignment to corporate goals is very much a human process. Are the HPM fanboy criticisms well founded or is it more a case that some BPM guys forget about strategic goal alignment and optimise process in isolation?

What do the facets say?

Clearly, there is a natural tension between these two polarities of BPM and HPM and this often plays out in organisational life in how we collaborate to deliver organisational outcomes. While there have always been process nazis, the emergence of social collaboration platforms that do not have a great deal of formal structure (think tagging and folksonomies) has led to a great deal of debate and self examination in BPM circles and beyond. Understanding these traits is critically important on the use of SharePoint tools, because SharePoint – and in particular SP2010 offers features for both BPM and HPM aficionados. Putting the two together however might risk Robot Barbie scenarios.

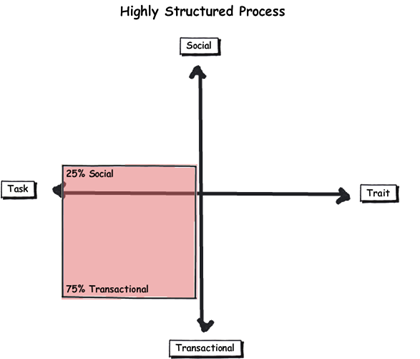

Straight away, it seems that the transactional vs. social axis of the facets of collaboration neatly explain the Business Process Management (BPM)/Human Process Management (HPM) challenge. Both areas are concerned with producing an output or getting something done. Therefore I have drawn BPM and HPM leaning toward the task side of the model. HPM proponents argue that human process is unstructured or semi-structured, dynamic, intertwined and borderless, which fits in well with the task/social trait of process and insight. BPM naturally fits into the lower transactional half where inputs are well defined.

While I would agree with the assertion that many processes are ill-defined and rely on tacit knowledge to be completed, HPM proponents go further though. For example, Ayal Steiner who I quoted earlier, argues that “analysts are now realising that human processes account for 80% of the business processes carried out in most organisations”. That is a big call, in effect, arguing that the majority of workplace interactions occupy the social quadrants above. I disagree. From my experience, most organisational roles have extremely varying degrees of transactional vs. social collaboration and some roles are in fact dominated by transactional collaboration. Perhaps there is some confirmation bias going on here, where knowledge workers who put in collaborative systems tend to think that everyone are knowledge workers too.

Here is an example. Mrs CleverWorkarounds used to be a medical nurse. When I first showed her this model I asked her to describe where nurses would fit in terms of their collaboration. She indicated two areas.

- Firstly, nurses are strongly linked by trait and transaction. This is because they all have a minimum degree of knowledge and skill. As stated in part 2, the key tell-tale sign of a role with transactional collaboration is how easily individuals performing that role can be replaced by someone else with similar experience at short notice. Supporting this, if a nurse is sick or unavailable, a replacement nurse can be called in to perform the same tasks. Collaboration between nurses according to Mrs Cleverworkarounds is quite transactional as well. Routine and process consistency via tracking the status of patient care is a critical task – patient status is everything. Thus, data driven tools with version history and well defined inputs make this form of collaboration easier. In fact, Mrs CleverWorkarounds taught herself InfoPath and SPD Workflows because she was so convinced that automated forms with consistent audit trails via workflow would make her job easier.

- Yet at the same time, the sort of collaboration between nurses and patients is completely different and highly social in nature. No process is going to govern the interaction between nurse and patient. The type of care and counselling to get someone well is going to vary the type of interaction. A broken leg is one thing, health problems from say – alcoholism is something else entirely. The latter has much deeper symptoms than just the illness as presented. Here the focus is on patient well-being and goes beyond status of meds, when doctors have visited or accurate handover notes from one nursing shift to another.

State machine workflows?

Interestingly, even seemingly well-defined business processes tend to have ad-hoc and dynamic aspects to them. When there is an exception to the standard process, those exceptions tend to be handled in a relatively ad-hoc, case-by-case manner. Microsoft developer Pravin Indurkar cited an example of a seemingly transactional purchase ordering system.

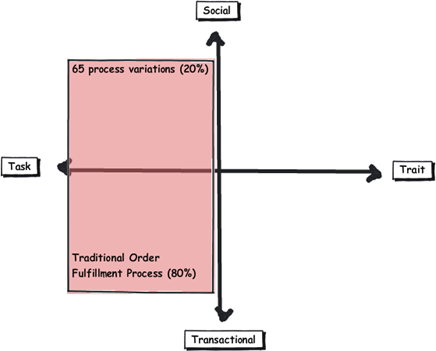

“Often the business processes contain a prescribed path to the end goal but then there are a lot of alternate ways the same goal can be achieved. For example, a purchase order can contain a prescribed path where the PO goes from being created, to approved, to shipped, and then to completed. But then there a multitude of other ways in which the PO can be completed. The PO can get changed, or back ordered or cancelled and then Reopened. All these paths must be accounted for.”

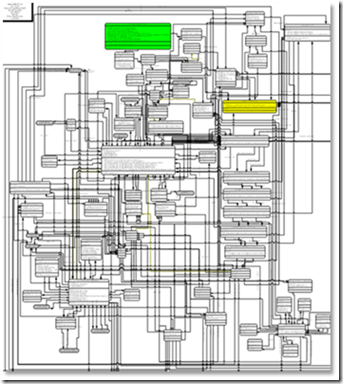

Indurkar studied the purchase order system of a small business and found that apart from the one standard traditional order fulfilment process, there were about 65 different variations on the same process depending on the nature of the order. This is when BPM diagrams start to get scary. If you think that this workflow below is scary, then be more scared. It is page 12 of a 136 page process!

Naturally, trying to hardwire such a large number of alternate paths is very difficult and traditionally, there were two ways in which this was dealt with;

- Either the business process was hard wired to accommodate all the paths as shown in figure 1, which made the implementation of the business process extremely complex, brittle and hard to maintain.

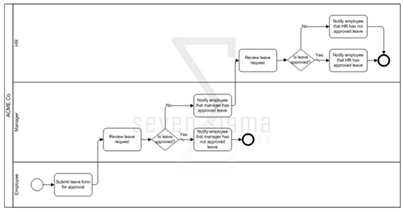

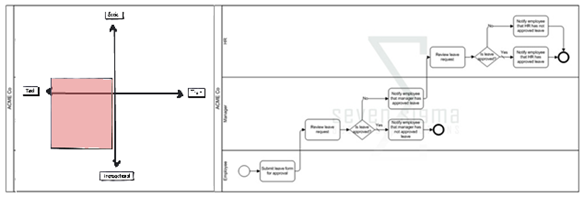

- The alternate paths are simply not dealt with and any situation of the ordinary was dealt outside the domain of the process. This meant that tracking and visibility were lost because people would create manual systems to track such out of the ordinary situations. The facet diagram below illustrates this:

In Indurkar’s article that I quoted with the purchase order example, he argued that the solution to this sort of problem was via state-based or state-machine workflows which SharePoint has supported in a basic fashion, out of the box since SP2007. This kind of workflow, if you are not aware, is when the workflow waits for one or more events to move it into another state. There is no sequence as such, because this new target state can be any of the defined states in the workflow. This makes state workflows reflect the unpredictable nature of process variations.

Thus, it could be argued that BPM is not incomplete as what the HPM fanboys think, but that critics have a less than holistic understanding of the craft?

Conclusion: A Process Analysis Tool…

To be honest, I don’t want to answer the question of which fanboy is right because it is a bit of a zero sum game. When you think about process, many seem to have elements of transactional and social in them (just like job roles). For example, an “Approval” decision diamond in a business process diagram will determine the path a process takes. Apart from stating the fact that this process is a gateway where a decision is made, this says nothing about whether the activity of making that decision is transactional or social. In some processes the decision may be made by a rigorous data driven process (like a point-score based credit check for a loan applicant). In others it may be on gut feel (such as choosing the right applicant for a job position).

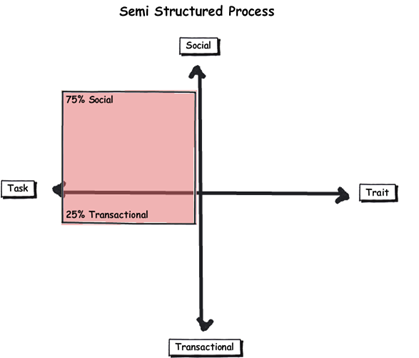

So to me, whether you are the most regimented process nazi or the most cowboyish non-conformist hippie, modelling a business process according to its ratio of transactional to social facets is probably very useful indeed to complement a BPM model. It help us understand how much tacit judgement is required in a given process and whether modelling every variation in a sequential workflow is worthwhile. Check out some examples on how this could be done below. In first example on the left, a business process where the majority of the steps are performed by tacit judgement might look like something like how I have drawn, with a task based social dominance. If the process in question indeed looks like this, then attempting to document every minute variation on the paths the process can take might not be worthwhile. Perhaps documenting the broad process (within the constraints of any compliance regime requirements) might be a better idea. In the second example, the process seems to be oriented around a repeatable set of choices (task based transactional dominant). As a result it may be worthwhile formally documenting these variations.

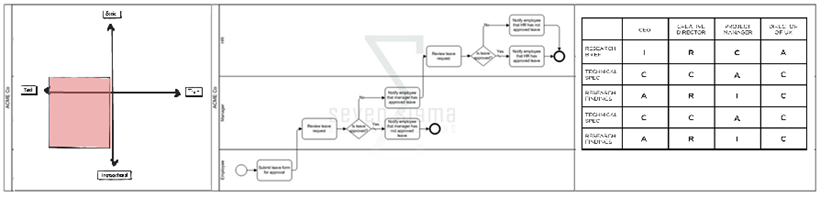

By combining these “process diagnostics” with the actual diagram, we might now offer additional insights into how the organisation really works with a certain process and do crazy stuff like produce something akin to my mockup below:

Hell, throw in a RACI chart and now you start to see process accountabilities as well!

Of course, you could always remove the task/trait axis if it is not needed and simply use a sliding scale. Nevertheless, what this shows is that the facets of collaboration model offers an extra dimension to any process being modelled and would help many to better understand the nature of the process being modelled, as well as strategies for improving that process via SharePoint.

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

p.s If you are a real trainspotter/glutton for punishment and want to dive deeper, google “Human Interaction Management” and “Role Activity Diagrams”

The DEMO methodology offers a well defined and structured way to analyse and model business processes the “Human Process Management” way.