The practice of Dialogue Mapping – Part 3

Hi there and welcome to part 3 of my series on the practice of Dialogue Mapping in the real-world. To recap, in part 1, I provided a brief overview of Dialogue Mapping and in part 2, I described a common real world usage scenario that we perform fairly often as SharePoint consultants.

The rest of this series will change tack a little. In this article I am going to describe a very different Dialogue Mapping scenario to you. This was a huge challenge and a large leap from what I described in part 2. There were some wonderful lessons learned from this work which I will cover off here.

The most “wicked” problems are not technical

My first Dialogue Mapping gig where I was not a subject matter expert also happened to be a real baptism of fire. Here was a problem that I had no understanding of, no discipline knowledge and no sense of background history of the project, the dynamics of the group, nor any idea of the positions of stakeholders on the problem.

By this time my IBIS fluency was pretty much down and I felt very confident with the usage of Compendium. I had not yet travelled to the USA yet to train under Jeff Conklin directly, but I carried his book around with me, and had read it many times over. I had performed Dialogue Mapping many times, however until this point all the projects or subjects that I was involved in I knew a lot about. This time I felt very vulnerable. Your domain knowledge is a form of armour, and it was unsettling to know that you’re going in stark naked. I was intimidated, yet excited at the same time.

So imagine this scenario. There was myself, a facilitator, and *fifteen* strangers sitting across from me. This was double the group numbers of the typical IT scenarios I had previously mapped. I remember emailing Jeff for advice when I heard that there would be so many and I recall him saying that 15 was a lot of people for a newbie. What was I in for! 🙂

Little did I know at the time that this group had been meeting for quite some time before that, but were really struggling on a complex urban planning issue. When I say complex, I mean complex in a social way, rather than technical. Interestingly, the issue was not a technically complicated issue at all. Anybody could have sat in the room and understood most of the dialogue (not necessarily the full context but you would not be completely blinded by science). What made this particular issue complex was the fact that the group members came from several different organisations, representing some quite diametrically opposing viewpoints. In part 2, I wrote about how it was hard enough just to get one IT department to come to the party and that was just one department of a single organisation – sheesh! If you have complained about organisational silos and think it is hard enough to get some degree of consensus within the realm of one organisation, imagine it when over a dozen representatives from different organisations are involved, organisations that straddle the full spectrum of public and private sectors, as well as the community.

There were simply so many stakeholders and interconnected issues that it was very hard to not get bogged down into tangents, repetition and frustration. Now, imagine eighteen months of this environment and the stressful social complexity impacts.

This is a long-term project that I am still involved with, so I will not be taking you through the specific details of this project just yet. Rest assured though, it has been such a great experience that I will write about it in detail in the future. For now, I will focus on lessons learnt so that others aspiring to perform this craft can learn from my own experiences.

People often tell you the best way to learn is to dive right in, and Dialogue Mapping is no exception. No sooner than I had put up a “what should we do…” type root question, it didn’t take long for debate to get … shall we say … rigorous! So I will go over some of the key lessons that I learnt from this experience thus far.

Lesson One: Confidence and assertiveness

The first thing that I had to contend with was not being in control of the conversation to the same extent as before. As previously stated, with SharePoint workshops I tend to direct the flow of the workshop as a mapper and as a subject matter expert. But this scenario was very different. I didn’t know the topic area at all and therefore some of the terms and acronyms made no sense to me. Also being new and unused to the decorum of the group, I erred on what I thought was politeness, rather than annoy the group by being direct and at times, interrupting them.

This, in my opinion, is a mistake and does a disservice to the other participants. It is also probably the most common thing a newbie mapper will experience when starting out, especially with a new group. As a result, the mapping in this first workshop ebbed and flowed. There were a few times where I was mapping the conversation really well, and the participants really engaged with the argumentation as it unfolded on the screen before them. Participants gestured to the map and asked me to add additional arguments and issues to what had already been built there. I could literally hear some of the initially sceptical, suddenly have that magic moment where they see it working. But at other times, during, say a particularly contentious issue, the conversation would fly at a rapid rate of knots. With so many people in the room, many wanted to have their say on these topics. This led to:

- Side conversations started up

- Some participants looked away from the map, and started debating directly to each other

As soon as one of these happened, and especially with the latter, I, as the Mapper, had no hope of following the conversation. As you might expect, I would lose focus and the quality of what was captured suffered (hence lots of idea nodes with no connections to anything). The focussing power of the map would be diminished and the wheels would start to fall off.

So remember this above all else. No matter what you do, you must be confident and assertive from the very start to keep the group focussed on the map. Don’t be afraid to interrupt someone to clarify a point, or pause them before they go too fast. If someone else starts to interject, interject back and make it clear that you will get to them as soon as you have finished capturing what someone else has said.

Here is the other critical thing: You must be consistent. It is the first ten to twenty minutes that will set the tone for the rest of the session. This is where people will implicitly learn the decorum of a Dialogue Mapping session and know what to expect. Your actions as a mapper, during this period, is critical to the overall quality of the session. Start it well and it will generally end well.

Jeff Conklin, of course, offers advice for this in his wonderful book on how to dealing with this. But of course, in the heat of dialogue, all of that advice goes straight out the window as you struggle to keep up with the rapid fire dialogue heading your way. Reading about how one should dialogue map is one thing, doing it is another. This is why I call Dialogue Mapping a craft and leads me to my second lesson learned.

Lesson Two: Remember that one guitar lesson you had? (Be realistic)

I think just about everybody at one point has had romantic notions of being a rock guitarist, banging out the blues like Clapton or blistering solos like Kirk Hammett or Brian May. A surprisingly large number of people have actually bought a guitar at some stage in their lives and have tried to live the dream. Most give it up once they find that the gap between their ability to play a G chord and their dream of playing the solo to Hotel California stretches to the moon and back. Inevitably, many guitars ends up collecting dust in the attic, along with the home gym set and many other items that were bought from late night infomercials.

You will hit this with Dialogue Mapping. Remember that wicked problems breed social complexity. Some problems may have some stakeholders with diametrically opposed views and discussion can be quite heated. The romantic notion of your group suddenly solving their wicked problem from your wonderful dialogue mapping has to be viewed with the reality that you still have to learn the G chord and audience can be fickle.

Thus, as far as audiences go, don’t go playing a stadium gig until you feel that you can handle sitting in the corner of a local bar or the school disco. In other words, start small and work your way up. A small, successful meeting will help you develop your style, confidence and then empower you to take on larger groups.

As Ali-G would say, keep it real.

Lesson Three: Stick to your domain of knowledge (at first)

This is a logical extension of lesson two, and also a tricky one because it can be just as much of a worst practice as a best one. This I suspect is probably a lesson on where Jeff Conklin or other dialogue mappers may disagree with me. One of the transitions that you have to make as a mapper is to move from what I would call Issue Mapping to real Dialogue Mapping. Just because you are doing mapping in front of a group, doesn’t actually mean you are necessarily “dialogue” mapping. Dialogue Mapping is often called “Issue Mapping with facilitation”, and when you work within your domain of expertise and you are a mapper as well as participant. Therefore you are not an impartial facilitator. This is the situation I described in part 2 and discovered very quickly, that pure dialogue mapping was much harder and mentally tougher.

But in terms of developing your skills, you will have good results when you are working in an area that you know well. You don’t have to worry about the meaning of acronyms and half of the questions you have likely heard before anyway. Remember though, that in a way it is kind of cheating because you are in effect, using the craft to get people to confront questions that you want answered. But it is an important stepping stone and will help you master lesson 4.

Lesson Four: IBIS grammar in the reptile brain

IBIS is the grammar that you use to map discourse. When mapping rapid-fire contributions from a group of people, they do not want to sit and wait for you to mull over whether their statement was an idea followed by a pro or an inferred question with an idea. If you find yourself having to do this, it is like trying to play a song on guitar and having to consciously think about how to play that G chord. Just think about how much you’d enjoy a Metallica concert if James Hetfield stopped every minute or so on a hard bit of a song and said “Wait, wait.. I’ve done this before… ok, hang on…oops, sorry”. This translation needs to burn itself into your reptile brain so that the process is as automatic as possible. To do this, you need to initially not worry about getting up in front of a group. As Conklin suggests in his book, listen to interviews on the radio or take an article, pull out its main points and create an IBIS map for it. There are a zillion ways to do this.

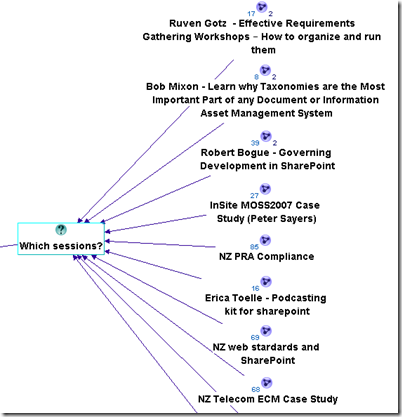

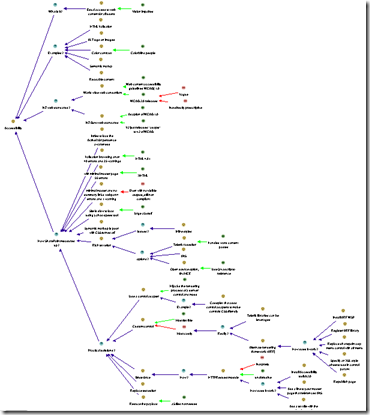

For all of you SharePoint people, a really excellent, highly relevant way of practice that I use, is to sit in the audience of a presentation at SharePoint Saturday or a conference and issue map the presentation. Below is a sample of some of the sessions where I have done this and the image after that demonstrates how much rationale I captured in the “NZ Web Standards and SharePoint” session.

Another great way to learn is to send one of your maps to an IBIS practitioner and let them pull it to bits. Even those of us who have done this for a while need that constant reinforcement and feedback. Like any grammar, different things can be written in different ways and one person’s IBIS will not always look like someone else’s. (There is another blog post in the works that will show this in a funny way). At various times I have sent maps to Conklin for constructive feedback (and then ducked for cover! – hehe)

Finally, if you are serious about this and like what you are reading, then do what I did – the 5 week Issue Mapping webinar based workshops that Jeff Conklin runs, or if you are in Australia and want something local, then contact me for a half or full-day in-house Issue Mapping intro workshop. Both will not teach you to dialogue map, but by the end of them you will dream in IBIS 🙂

Lesson Five: IBIS translation in the reptile brain

Once the language of IBIS is familiar to you, you can take any argumentation and form a consistent IBIS map. You then have to learn how to listen very carefully because that is half the art. Now you have to take prose and pontification by participants and somehow unpack the points made, articulate them into a summary, and form an IBIS based model in your head, and then commit it to the map.

This can be hard – very hard, and it is nigh on impossible to do without applying what I told you in lesson one. A dialogue mapper is not superhuman and does not have photographic memory. The skill you are developing here is one where you pick out the IBIS elements of some dialogue quickly, as well as knowing when to interject to make sure you do not miss anything.

A great example of this working is when someone has stated something, and although I cannot remember all points, I know that there was a question and three ideas offered. I might pause the conversation before it goes too far and say something like “Ah, that was important and I need to get this right. I heard you say three things there. You questioned the idea of X, and you offered an answer with 3 pros. One was Y, and what were the other two again?”

Conklin explains meeting discourse and question types in his book and the aforementioned workshop in a lot of detail. But once again, to apply it to a real-world situation can only be done by practice (and more practice). The absolute best way to do this is to watch an experienced dialogue mapper perform this and look at how they handle the situation, which brings me onto lesson six.

Lesson Six: Observe

One of the most enjoyable training experiences of my career was to travel to the picturesque town of Annapolis and learn dialogue mapping from Jeff Conklin himself. Up until then, I had been practicing the craft, but after those two days, I returned as a much better practitioner.

The single most important part of the time spent there was when we, the students, dialogue mapped each other as we discussed a real-world issue. We each sat in the hot seat for fifteen minutes or so, trying to map the discussion. We were all being completely evil, deliberately starting side conversations, interrupting and interjecting, playing the role of the dominant type A style participant, jumping all over the place and, overall, just being as difficult as we could.

Unsurprisingly, we all sucked big time trying to dialogue map this. However, when Conklin took the floor, we then saw how exactly Dialogue Mapping was done and what twenty years of practice does. He effortlessly brushed off our attempts to trip him up by observing all of the lessons that I have thus far described, but also with some subtle tricks that we didn’t even notice until he told us afterwards.

After Conklin had wiped the floor with us, so to speak, we all got to have another crack at it, with the benefit of observation and hindsight. This time the difference was significant in our performance and the way that we each handled the “mob”.

Moral? The very best thing you can do is to be involved in a Dialogue Mapping session where it has been done well. Watch carefully what the mapper is doing and how they are conducting themselves and the process.

Lesson Seven: It will make you tired

If you think of all the various things that you have to do simultaneously (for examples listening, understanding, mapping, and managing the group) during Dialogue Mapping, it is amazing that anyone with a Y chromosome can manage it, given that men usually cannot multitask at all. (Case in point: If sport is on the radio and my wife is speaking to me, one of them has to be switched off…Sorry honey 🙂 ).

When you are first learning this craft and you are going to be up in front of a group, plan for only an hour or so. While you have to think quite consciously about things, it will exhaust you even more. Once things become more automatic, you can go for longer. From my own experience, the limit for Dialogue Mapping a big group on a really wicked topic would be about four hours at the absolute maximum. (Usually by then the participants also need to take a break and sleep on it anyway).

Some sessions can be intense, and you, as a mapper, need to be switched on for that entire time. You are listening carefully to every person speak because you are trying to form it into IBIS. So unlike everybody else who can sit there and look interested, yet be mentally switched off, you have to be interested by definition.

One thing about this is that, while you are in the zone, you don’t need coffee. When mapping, you have enough endorphins racing around your system to keep quite alert, but as soon as there is a break, you can find that you will feel quite tired at times, and a well timed coffee can be very handy (real coffee, of course – none of that instant junk!)

The one thing that compensates for what Dialogue Mapping can take out of you mentally, is that exhilarating experience when the group is really getting into the process and the positive feedback that you receive when a really well formed map has been developed.

Lesson Eight: Learn to love “transclusions” and CTRL+R

I thought that I would drop in a left-field lesson learned at this point that is still very important.

Trans-what? Don’t worry – I don’t know why they called it that either. Ted Nelson, who also coined the term “hypertext”, came up with the name but I think the day “transclusion” sprung to mind, he was having an off-day. I asked Conklin what it meant and he said “It’s technically accurate … an "inclusion" of material *across* (‘trans’) several documents”. When I whined about the geekiness of the name he added “There was a time when the word "hypertext" was a wacko term for geeks, you know”. Damn! He’s got me there.

My explanation that will suffice for now? Transclusions is a fancy way of describing the process of breaking your big map up into smaller, linked up sub-maps. I have also heard it referred to as chunking, and when maps get too big, this is a necessity. (For the hypertext nerds that is somewhat incomplete but suffices for this point).

The compendium software that I choose to use for this work also has a great feature in it. Your map is re-drawn automatically when you hold down the control key and press R. I am now in the habit that after entering a node or three, I redraw the map via this method to keep it all looking orderly. That way, if there has been a lot of dialogue captured, you do not end up with a messy, cluttered map that participants find hard to follow. Like lesson number three and four, stopping conversation while you refactor a messy map will cost you group momentum so ideally if you have gotten into the Control+R habit, all you have to do is a quick transclusion at an opportune time.

The best time to perform a map transclusion is when a thread of discussion has been exhausted and the group has moved onto a new idea or area in the map. A trick I learned from Anapolis was to sit up and say something like “Okay, let’s just pause for a minute.” (Holding up my hand), congratulate the group on the quality of what they have captured and then say something like “Let’s just put this stuff into its own pigeonhole, so we can now focus on X idea”.

Lesson Nine: Nurture the holding environment

Okay, so if there is to be one big serious lesson learned, it is this one. To make the point, I am going to quote Heifetz and Linsky from their excellent book Leadership on the Line. You can read a PDF press release here, specifically the section entitled “Control the temperature.”

Changing the status quo generates tension and produces heat by surfacing hidden conflicts and challenging organizational culture. It’s a deep and natural human impulse to seek order and calm, and organizations and communities can tolerate only so much distress before recoiling.

If you try to stimulate deep change, you have to control the temperature. There are really two tasks involved. The first is to raise the heat enough that people sit up, pay attention, and deal with the real threats and challenges facing them. Without some distress, there is no incentive for them to change anything. The second is to lower the temperature when necessary to reduce a counterproductive level of tension. Any community can only take so much pressure before it becomes either immobilized or spins out of control. The heat must stay within a tolerable range—not so high that people demand it be turned off completely, and not so low that they are lulled into inactivity.

Heifetz and Linsky talk about maintaining the “the productive range of distress” but I have heard many metaphors like this. Another I like is “creative abrasion”, coined by Leonard and Swap in their excellent book When Sparks Fly . Both are essentially talking about making the whole environment conducive to getting the best out of the participants.

The key takeaway is this: Each group is different and each situation is different. In the normal discourse of the meeting, there will be times where the group works together in almost perfect unison and times where one wrong word will destroy that balance and require the group to stop, reset things and move forward. This is not about IBIS either. The fact is that over time, a particular pattern will emerge in the decorum of the sessions, where conducting the sessions or approaching the mapping in a particular way, will work consistently well for the group.

Let me give you a classic example that was absolute genius on the part of my client who did exactly this. Before Dialogue Mapping for a group of concerned residents who were facing the prospect of significant change to the amenity of their homes, a bus was hired and the residents were taken to an area where a similar urban transformation had been made ten years before. We all walked around the area for an hour, soaking in the vibe, learning about the history of the area, how the area was redeveloped and how certain planning challenges were overcome.

This allowed the participants to get a real sense of the issues they needed to confront, and they felt it with all senses, sight, sound and tactile, rather than some cold, rather detached room with a projected map on the wall. Later, when I dialogue mapped the session after the bus tour, the group did a fantastic job and the quality of the rationale that was captured was much richer and faster, through that sensory immersion that took place before the mapping process began.

So just remember, Dialogue Mapping is a great holding environment in the sense that Heifetz and Linsky talk about. It is a wonderful “rich container”, as Conklin puts it, for fostering and maintaining creative abrasion. But as the bus ride example shows, there is a lot of things that you can combine with it to enhance the experience further.

More examples like this will be covered in part 4 of this series.

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

Paul,

Thanks for this post. You’ve outlined some excellent, not-so-obvious tips for novice dialogue mappers such as myself.

Regards,

Kailash.

Personally my favorite IBIS blog post yet as this is stuff that is information that is hard to find, and even harder to ‘get’ and put into practice. You did a great job explaining and giving examples on many of these points.

Looking forward to using IBIS mapping more and more in the future (and with these tips well executed, more effectively),

Richard Harbridge

Hi Paul. Can you provide instructions for creating “transclusions”, as you describe: “breaking your big map up into smaller, linked up sub-maps”? This is a blocking issue for me, when dialogue mapping. I’m stuck with this large, unwieldy map.

I’ve looked at the Compendium help file, but the answer’s not jumping out at me. It’s like standing at the decongestants aisle in the pharmacy. I know the answer’s there. I just haven’t found it. 🙂

Thanks,

Rob Schmidt

Hiya (this will make you laugh)

1. Choose the node that represents the point that you want to put into a sub-map. Hold down alt when clicking it so all sub nodes get selected.

2. Control+C

3. Click a blank area of the map and type the letter M and name it “Discussion on [x]”

4. Double click the map node and the sub map opens

5. Control+V

6. Close the sub map and go back to the parent map

7. Hold ALT and select the node you selected in Step 1

8. Hold Shift and click the node again (all sub nodes should be selected but the head node now should not be

9. Press delete key

10. Link newly created map node to the remaining node

regards

Paul

p.s You can do it with Control X but better to be safe then sorry

Thanks Paul. That worked great. Sometimes it’s the most simple solution that’s elusive.

– Rob Schmidt

Another tip, in the compendium project or user options (forget right now), you can set the icon size of nodes. Set it to small size and you will make better use of screen real-estate

Great blog post, really useful!

Finding out that holding Alt and selecting a node selects all the sub nodes can be really useful! (comments section). From that I figured out that Shift Alt selets all the parent nodes leading to the top. That could be useful for highlighting where this goes to.

Keep up the great work Paul!